Many of our long-time readers know I enjoy highlighting women résistants in the French Resistance. Stories like Nancy Wake (read The White Mouse here), Suzanne Spaak (read Something Must Be Done here), Marie-Madeleine Fourcade (read Noah’s Ark here), and Hélène Berr (read The French Anne Frank here) are quite uplifting and show the superior leadership skills, moral commitment, and fortitude these women possessed.

Today, you’ll be introduced to an exceptional résistant who was the only woman to actually lead a Special Operations Executive (SOE) circuit (i.e., network) as well as being responsible for leading a large group of Maquis (French Resistance underground guerrilla fighters) before, during, and after the Allied invasion on 6 June 1944.

Did You Know?

Did you know that the Wallace fountains in Paris are painted bright primary colors? The original paint was what we call today, “British racing green” ⏤ remember Jim Clark’s Formula One racing car from the 1960s? Yes, of course, you do (that is why I inserted a picture).

About three years ago, I wrote a blog on the Wallace fountains (read Wallace Fountains here). Readers were introduced to Sir Richard Wallace (1818-1890), a British philanthropist who was concerned about the lack of safe drinking water in Paris. He financed the building of public drinking fountains which have become affectionately known as “Wallace Fountains.” As Ulrike explains in her article (see below), some of the fountains have been painted in bright colors. It’s easy to miss the green fountains but there is absolutely no way you can miss the bright red, yellow or purple ones!

Please enjoy this article written by Ulrike Lemmin-Woolfrey: click here.

If you enjoy Paris and haven’t already done so, I recommend you subscribe to the Bonjour Paris blog. Link here.

Special Operations Executive

The SOE was officially formed on 22 July 1940 when Winston Churchill ordered Hugh Dalton to “set Europe ablaze.” Churchill loved the idea of spies, espionage, and guerilla warfare. At the time, the British military leaders were against it as it represented irregular warfare tactics, but Churchill knew that undercover covert operations within the occupied countries would be necessary to accomplish the Allied goals, including the eventual invasion of Europe.

Every occupied country was represented by a separate SOE department ⏤ France was represented by “F Section.” Approximately 13,000 people worked for the SOE, of which 3,200 or 25% were women. Most of the agents were people who had been driven out of their countries and could blend in easily with the locals. Although the SOE was headquartered at 64 Baker Street, hundreds of properties were requisitioned throughout England and Scotland for training its agents in hand-to-hand combat, parachuting, demolition techniques, commando tactics, and radio-related skills.

At times, the SOE was referred to as the “Baker Street Irregulars” (after its London headquarters), “Churchill’s Secret Army,” and “Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare.” Underground circuits or networks were set up in the occupied countries with teams of three agents (an organizer, radio operator, and courier) sent in for the purpose of gathering information, assisting with the escape of downed Allied airmen, and sabotage. The Gestapo was quite effective, especially in the Occupied Zone of France, with infiltrating and ultimately, destroying whole circuits (the average life span of an SOE agent was six weeks to three months). As time went on, some of the SOE agents became Nazi informants or double agents (read Double Agent or Bad Neighbor? here and read The Double Cross System here). Through the “Funkspiel” program (also known as “Englandspiel” in Holland), the Germans were able to capture SOE radios, codes, and deceive London with false transmissions.

Probably the most productive efforts contributed by the SOE came in late 1944 and early 1945 just prior to D-Day when agents were dropped into France to assist the Maquis in their efforts against the Germans (read The White Mouse here). During the months and days leading up to D-Day, the SOE and Maquis activities likely helped ensure the success of the invasion and saved countless Allied lives.

Let’s Meet Pearl Witherington

Cécile Pearl Witherington (1914-2008) was born and raised in France but as a child of British expats, Pearl held dual citizenship: British and French. Her father was rich, but he was a drunk and eventually, burned through the family’s wealth. He died early leaving Pearl to assist her mother with three younger daughters. Employed by the British Embassy in Paris, Pearl was able to flee Paris along with her mother and sisters in December 1940. Arriving in England, Pearl was determined to find employment which offered her a meaningful avenue to fight the Nazis and their occupation of France. Despite some roadblocks, Pearl was persistent and found her calling with the SOE.

“Marie”

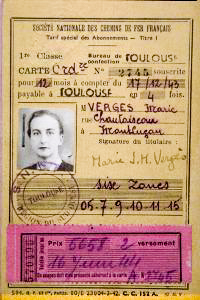

Pearl flunked Morse Code during her SOE training and her sponsors thought she didn’t have leadership skills. This eliminated her for positions as an organizer (circuit leader) and radio operator. It was noted in her file that Pearl was one of the best shots in her class. She was assigned as a courier to the Stationer circuit run by her childhood friend, Maurice Southgate (1913-1990). Stationer had responsibility for the south and central parts of France reaching down to the Pyrenees. In other words, the territory was huge, and Southgate needed a lot of help. Pearl parachuted into southern Loire, France on 22 September 1943 and immediately began her duties as Southgate’s courier. The British recognized Pearl’s nom de guerre as “Marie” while the French came to know her as “Pauline.”

On 1 May 1944, Southgate (“Hector”) arrived at a meeting after missing the secret signal that the Gestapo was there waiting for him. He was captured, deported to Germany, and endured the hardships at Buchenwald concentration camp. Unlike other foreign agents who were executed at the camp, Southgate survived the war. However, SOE had an immediate problem. The Stationer circuit had been compromised and thousands of agents’ lives were at stake. The solution was to split Stationer into several smaller circuits; one of which was the Marie-Wrestler network operating in the Valençay-Issoudun-Châteauroux triangle in central Loire Valley. Pearl was put in charge of the roughly 1,500-member circuit and immediately divided it into four Maquis groups. Her fiancé, Henry Cornioley, joined one of the groups. Pearl’s leadership led to highly specialized sub-circuits and soon, the combined manpower under Pauline totaled nearly three thousand. The Wrestler circuit was so potent that the Gestapo posted a one-million-franc reward for her capture. Pearl was never betrayed.

During the time Pearl ran Wrestler, the primary mission for the various Maquis groups was to prepare for the invasion. Their tasks were assigned by London with the express purpose of slowing the advancement of German troops and tanks towards the Normandy beaches (read Dah-Dah-Dah-Duh here). This was accomplished through acts of sabotage including cutting rail tracks. Wrestler was responsible for more than four hundred acts of sabotage in the month of June 1944 alone.

Watch a video on Pearl here.

After The Invasion

Several days after D-Day, Pearl learned that some of the Maquis groups had not carried out their assignments which she soon came to realize meant that German soldiers would track her men down. Her fears became reality on 10 June when seven thousand Wehrmacht soldiers descended on her territory. She and forty of her men were surrounded and the fighting lasted fourteen hours. They lost half their men while the German casualties were 286. Pearl and the others disbursed after the German soldiers withdrew and the next day, the Germans returned to destroy Pauline’s headquarters, the Château des Souches, and blew up the Maquis arms depots in two locations. Captured German soldiers would later admit they thought they were fighting nearly three thousand Maquis guerillas.

After this “little” skirmish, Pearl decided to request that a trained military officer be assigned to Wrestler to lead the men in combat. She took on the traditional SOE role as liaison between London and Wrestler in providing weapons, cash, and supplies to the Maquis. By mid-August, Pearl learned about a German train convoy of twenty tank cars carrying fuel to the front line. Pearl alerted London and the RAF was successful in destroying the fuel shipment. Wrestler was one of the Maquis groups which forced the surrender on 14 September 1944 of 18,000 Wehrmacht soldiers at Issoudun. After the war, it was clear the French Maquis not only liked Pearl, they respected her.

Post-War

Pearl returned to England in September 1944 and within a month, married Henry Cornioley. Henry went on to a post-war career as a pharmaceutical chemist while Pearl worked for the World Bank in Paris. In retirement, she remained active in various organizations dedicated to preserving the memory of the SOE and its agents. Pearl teamed with Hervé Larroque to publish her autobiography in 1997.

Parachute Wings and Other “Civil” Honors

As part of her SOE training, Pearl was required to take parachute lessons (agents parachuted into France). These lessons required five jumps: four training and the fifth one was operational (i.e., the jump into France). Pearl only did three training jumps before the operational one. After the war, the British government refused to issue her the formal Parachute Wings since Pearl had only completed four jumps and not the requisite five to earn the wings. Sixty-one years after the end of the war, Pearl was finally awarded her Parachute Wings ⏤ the one medal or insignia she treasured the most.

After she returned to civilian status, Pearl was recommended for the British Military Cross (MC) but unfortunately, the MC could not be awarded to a woman at that time (the rule was changed and the first woman was awarded the MC in 2006). As the “consolation” prize, the government offered Pearl “The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire” or, MBE. There are two types of MBE: military and civil. They offered Pearl the civil MBE which she rejected. Her response was, “There was nothing remotely civil about what I did. I didn’t sit behind a desk.” By 2006, Pearl was awarded and accepted the military MBE and Queen Elizabeth II personally awarded Pearl the “Commander of the Order of the British Empire” or, CBE. The Queen told her, “We should have done this a long time ago.”

The French government awarded her the Medal of the Resistance, the Croix de guerre, and the Legion of Honor.

Henri Cornioley passed away in 1999 with Pearl following in 2008 at the age of ninety-three. They were survived by their daughter, Claire.

✭ ✭ ✭ Learn More About Pearl Witherington ✭ ✭ ✭

Atwood, Kathryn J. Women Heroes of World War II. Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2011.

Bourne-Paterson, Major Robert. SOE in France 1941-1945. Yorkshire, UK: Frontline Books, 2016.

Cornioley, Pearl Witherington. Edited by Kathryn J. Atwood. Code Name: Pauline: Memoirs of a World War II Special Agent. Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2013.

Rossiter, Margaret L. Women in the Resistance. New York: Praeger Publishers, 1986.

Sebba, Anne. Les Parisiennes: How the Women of Paris Lived, Loved and Died in the 1940s. London: The Orion Publishing Group Ltd., 2016.

Seymour-Jones, Carole. She Landed by Moonlight: The Story of Secret Agent Pearl Witherington: The “Real” Charlotte Gray. London: Hodder & Stroughton, 2013.

The book Code Name: Pauline is based on the in-depth interviews conducted with Pearl in the 1990s by Hervé Larroque. The original interviews were published in 1995 as Pauline. This book, edited by Ms. Atwood, is based on those interviews. Ms. Atwood is the author of a series of books on women heroes in various conflicts.

What’s New With Sandy and Stew?

Sandy and I recently got our new puppy, Stella. She is a beagle and we love her. Stella is one smart cookie and already rules the Ross household. It has been three years since we lost our beloved beagle, Lucy. While it is always natural to make comparisons, each day goes by and we can see the uniqueness which Stella brings to the Ross family. Hope you don’t mind me sharing her picture with you.

Someone Is Commenting On Our Blogs

Thank you to Camille who contacted us about our blog, Picasso’s Wartime Man Cave (read here). Camille shared a story about the building where Picasso holed up during the Nazi Occupation. It was the story of Antoine Duprat (1463-1535) whom François I appointed Chancellor of France and prime minister. As she pointed out, Paris has so much more history than Picasso and the Nazis. I couldn’t agree more with her. That is one of the reasons why I decided to write the series of books on Paris. Thanks again Camille and I hope you’ll subscribe to our bi-weekly blog.

If there is a topic you’d like to see a blog written about, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I love hearing from you so keep those comments coming.

Why Would You Want To Buy Our “Walks Through History” Books?

Simple.

You like to travel and experience history and historical events. You like to see original buildings that had a significant impact on the people and events of the history you’re engaged with. You want to know the stories behind the brick and mortar in front of you.

The walking tour books are meticulously researched so you can go directly to those sites and learn about the building’s history as well as an introduction to some of the more interesting people associated with it.

We Need Your Help

Please tell your friends about our blog site and encourage them to visit and subscribe. Sandy and I are trying to increase our audience and we need your help through your friends and social media followers.

Thank You

Sandy and I appreciate you visiting with us. We have some exciting things on the horizon and we’ll keep you updated as we go along.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and iBooks.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs.

Walks Through History

Walks Through History

Copyright ©2019 Stew Ross